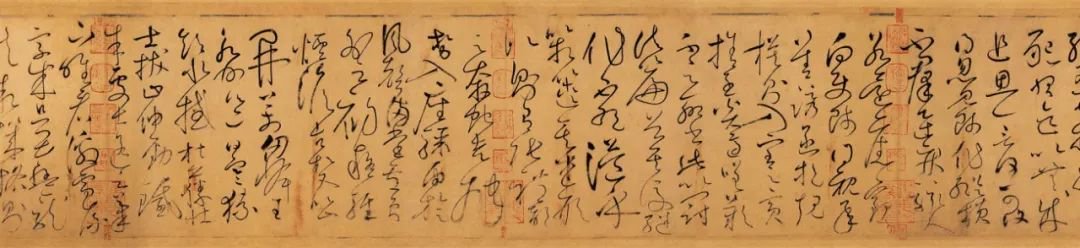

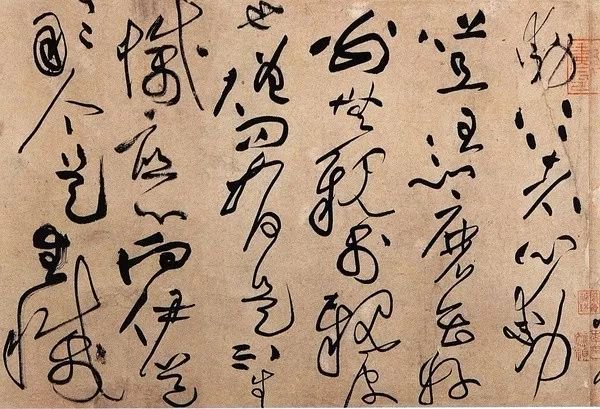

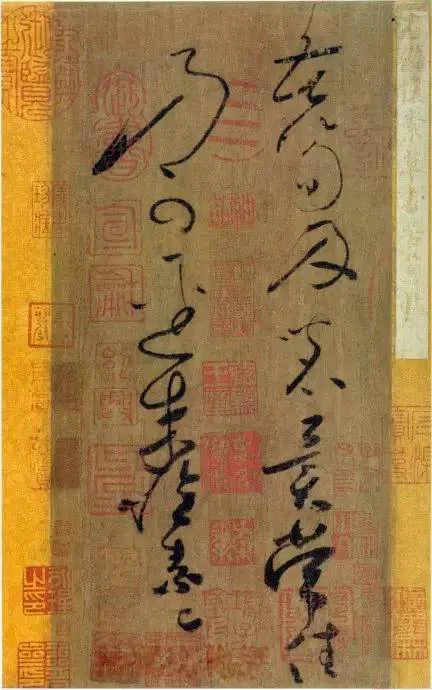

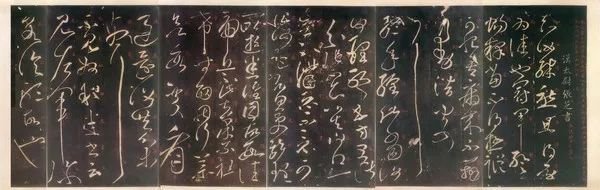

Huai Su's cursive script "Kushu Tiejuan"

Chinese cursive script is a calligraphy style of Chinese characters. It is the most difficult and demanding calligraphy style in Chinese calligraphy in terms of artistic expression. It is characterized by simple structure and continuous strokes. It was formed in the Han Dynasty and evolved on the basis of official script for the convenience of writing. There are Zhangcao, Jincao and Kuangcao.

There are rules and regulations to follow when making changes in Zhangcao's strokes. Representative works include the Songjiang version of Wu Huangxiang's "Jijiuzhang" of the Three Kingdoms. Jincao's writing style is informal and smooth, and his representative works include "Chu Yue" and "De Shi" written by Wang Xizhi of the Jin Dynasty. Kuangcao appeared in the Tang Dynasty, represented by Zhang Xu and Huaisu, with wild and uninhibited writing styles, and became an artistic creation that was completely divorced from practicality. From then on, cursive script was just a calligraphy work that calligraphers copied from Zhangcao, Jincao and Kuangcao. Kuangcao's representative works, such as "Belly Pain" by Zhang Xu of the Tang Dynasty and "Autobiography" by Huai Su, are all extant treasures.The greatness of cursive script is that it uses the simplest and most direct dots to express people's mental images. As a result, cursive writing has become the most expressive and condensed abstract art in the world. Xu Shen's "Shuowen Jiezi Shu" says: "Cursive script appeared during the rise of Han Dynasty", which should refer to Zhangcao. Zhang Cao's extreme norms have restricted its own development. Nowadays, because of the full freedom of expression and the development of laws, the grass can be divided into big (crazy) grass and small grass. In the process of evolution for nearly two thousand years, a large number of masterpieces by famous artists have been produced that shocked the past and the present. Today, cursive script, with its highly concise form and sustainable development characteristics, echoes and blends with the times and modern art, revealing its greater and more lasting artistic charm!

The important ones are listed below

At least 11240-8864 BC

The pictures and characters of the Damaidi rock paintings in Zhongwei, Ningxia, discovered in 1988, are at least 5,000 years older than the oracle bone inscriptions. They are very likely to break the "Western language" of Chinese characters and are recognized as one of the sources of Chinese characters. These pictures and characters are mostly pictographic and almost the same as paintings, which can be regarded as ironclad evidence that calligraphy and painting have the same origin. According to legend, the dragon saw the eight ears of golden crops and wrote the ear script, the Yellow Emperor saw the scenery and clouds and wrote the cloud script, Shaohao wrote the luan and phoenix script, and Emperor Yao wrote the turtle script. They have the meaning of seeking beauty, or they may be the curse of cursive script.

Early Shang Dynasty: 1600-1300 BC

The ink ink writing on oracle bones discovered in 1899 proves that our ancestors were already using brushes at that time.Before Emperor Zhang of Han Dynasty: 102 BC - 87 AD

A large number of Juyan and Dunhuang bamboo slips unearthed in modern times, such as bamboo slips from the third year of Taichu, the first year of Taishi, the fourth year of Shenjue, the third year of Yangshuo, the third year of Jianwu, the fourth year of Yuanhe, etc. , it can be seen that there is an obvious tendency of cursive writing in the Han Dynasty, which is the origin of real cursive writing.

Emperor Han Yuan: 48-33 BC

Shi You wrote "Jijiupian", "disbanded the official style and wrote it in rough script", which was later called Zhangcao. The "Jijiupian" we see now was copied after the Song Dynasty and is said to be the "ancestor of Zhangcao". In fact, it may not come from the old Shiyou edition.

Emperor Zhang of the Han Dynasty: AD 76-87

Du Du is good at cursive calligraphy and is known as the "Sage of Cursive Calligraphy". But no works have been handed down. Liu Da, the Emperor of Zhang, was also known as a good calligrapher, and he was particularly fond of Dudu's cursive calligraphy. There is a "Thousand Character Essay" handed down from generation to generation, and "Chunhua Pavilion Notes".

The fifth year of Emperor Yongyuan of the Han Dynasty: 94 AD

The compilation of Yongyuan's utensils book unearthed in Juyan, although it is written in Zhangcao, is written in a very free and unrestrained style, which is the first of its kind in later generations.

The first year of Yuanxing, Emperor He of the Han Dynasty: 105 AD

The paper made by Cai Lunshang was called "Caihou Paper" at that time. Since then, later generations have always used paper as the main material for writing.

From Emperor An of the Han Dynasty to Emperor Xian: AD 107-220

Zhang Zhi (? - about 192), courtesy name Boying, was from Dunhuang. He is proficient in cursive writing, and calligraphy history says he is better than "one-stroke calligraphy", so he is known as the "Sage of Cursive Calligraphy". Wei Heng's "Four Body Scripts of Calligraphy" said that he "learned calligraphy near a pond, and the water in the pond was full of ink." The handed down works include "Champion Tie", "Qiuliang Pingshan Tie", "Message Tie", etc., all of which are recorded in "Chunhua Pavilion Tie". Although not entirely credible, they are a portrayal of the prosperity of cursive script at that time.

Emperor Ling of the Han Dynasty: 168-189 AD

Zhao Yi (birth and death unknown) wrote an article "Not in Cursive Script", which criticized the learning and creation of cursive script that had become a trend at that time. His intention is to restore ancient times and promote Taoism, and he is opposed to playing "cursive script" and getting discouraged. However, he failed to fully realize the artistic magic of cursive script and the principle of unity between Taoism and art, and ultimately could not stop the flourishing development of cursive script art.

Three Kingdoms/Wu: AD 220-280

Huang Xiang (birth and death unknown), courtesy name Xiu Ming, was born in Jiangdu, Guangling. He is good at cursive calligraphy, and his works include "Jijiupian" and "Team Notes for Civil and Military Generals".

Western Jin Dynasty: 265-317 AD

Wei Guan (220-291), courtesy name Boyu, was a native of Anyi, Hedong. He wrote "State People's Post".

Wei Heng (?—291), whose courtesy name is Jushan. He is the author of "Four Body Scripts", one of which discusses cursive script.

Yang Quan (birth and death unknown) is the author of "Fu in Cursive Script".

Suo Jing (239-303), courtesy name You'an, was from Dunhuang. He learned from Zhang Zhi and was good at cursive calligraphy. His works include "Ode to the Master", "Yueyi Tie", "Gaotao Tie", etc. He is the author of the article "Cursive Script".

Lu Ji (261-303), courtesy name Shiheng, was a native of Wu County. "Pingfu Tie" is the earliest calligraphy ink on paper handed down to the world (now in the Palace Museum). Between Zhangcao and Jincao, his writing is vast and honest, and contains the meaning of seal script, which occupies an important position in the history of calligraphy.

Eastern Jin Dynasty: 317-420 AD

Wang Xizhi (307?-365?), courtesy name Yishao, was originally from Langye, Shandong, and lived in Kuaiji, Zhejiang. He was a great calligrapher in the Eastern Jin Dynasty and was respected as the "Sage of Calligraphy" by later generations.

In the ninth year of Yonghe: before 353 AD, Wang Xizhi wrote "Xing Rang Tie", "Chu Yue Tie", "Seventeen Tie", "Yuanhuan Tie", "Youmu Tie", "Duxia Tie", "July 1" "Ri Tie", "Bao Nu Tie", "Shi De Shu Tie", "Xiaoyuan Tie", etc.

The fourth year of Shengping: 360 AD

Wang Xizhi's book "Han Qie Tie".

Wang Xianzhi (344-388), courtesy name Zijing, was the seventh son of Xi Zhi. The books include "Ge Qun Tie", "Yatou Fan Tie", "Xianye Tie", "Chujie Tie", "Thinking of Bi Tie", "Zhu Shan Tie", etc.

Southern Dynasties/Liang Dynasty: 502-557 AD

Xiao Yan (464-549), Emperor Wu of Liang Dynasty, wrote "Beriberi Tie" and wrote "Cursive Script".

Sui Dynasty: 581-618 AD

Monk Zhiyong (?—?), whose books include "Zhencao Thousand Character Essay" (a masterpiece of Xiaocao, the ink copy is now in Japan) and "Huan Lai Tie".

Tang: AD 618-907

Ouyang Xun (557-641), courtesy name Xinben, was born in Linxiang, Tanzhou. Among the books are "Thousand-Character Essay in Cursive Script" (a printed version that exists today).

Tang Taizong Li Shimin (599-649)

The books include "Screen Post" and "Last Night Post".

Lu Jianzhi (?—?) wrote "De Announcement".

Li Huailin (?—?), whose book is "Book of Breaking Diplomacy".Chuigong three years (687):

Sun Guoting (648-703), whose courtesy name was Qianli, was born in Chenliu. The long scroll of "Shupu" written in that year is filled with thousands of words. It is not only a masterpiece of small works, but also an excellent masterpiece of calligraphy theory. It is praised by later generations as a "double gem".

The first year of Shengong (697):

Wang Fangqing presented a total of ten volumes of writings from twenty-eight members of the Wang family, the eleventh generation ancestor of the Jin Dynasty. Wu Zetian ordered them to copy and keep the contents, which is the "Long Live Tongtian Tie" (now in the Liaoning Museum). The original copy was returned to Fang Qing. Among them, in addition to Wang Xizhi's "Chu Yue Tie", there are also cursive scripts such as Wang Hui's "Boil and Swelling Tie", Wang Ci's "Debai Wine Tie", "Rubi Tie", and Wang Zhi's "One Day Without Application".

He Zhizhang (659-744), whose courtesy name was Xiuzhen and also known as "Siming Kuangke", was a native of Yongxing, Yuezhou. The book (biography) includes "The Classic of Filial Piety".

Li Bai (699-762), courtesy name Taibai and Qinglian Jushi, was a native of Shu County. The books include "Shangyang Tie" and "Guanshen Tie" (engraved editions are preserved today).

Zhang Huaiguan (?—?) was from Hailing. Calligrapher and calligraphy theorist in Kaiyuan Dynasty. He is the author of "Calligraphy Instruments", "Six-Style Calligraphy Theory", and comments on cursive script evaluation, etc., which can be used as a reference.

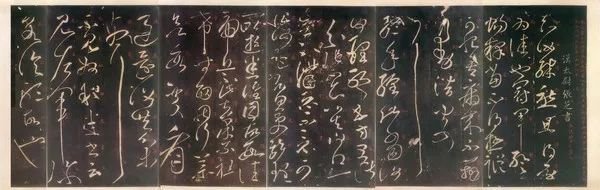

Zhang Xu (?—?), courtesy name Bogao, was born in Wuxian County, Suzhou. He is addicted to alcohol and often goes crazy when drunk, sometimes shouting "Zhang Dian". The books include "Tie of Belly Pain", "Tie of All Years", and "Thousand-Character Essay" (old fragmentary edition). Another book passed down is the ink mark of "Four Notes on Ancient Poems" (now in the Liaoning Provincial Museum).

Taihe (827-835)

Li Fang, Emperor Wenzong of the Tang Dynasty, ordered Li Bai's poetry, General Pei (Min)'s sword dancing, and Zhang Xu's cursive calligraphy to be the "three wonders".

Tianbao twelve years (753):

"Miaofa Lotus Sutra Xuan Zan Volume" was written (one of the Dunhuang sutras discovered in modern times).

Yan Zhenqing (709-785), named Qingchen, was a native of Linyi, Langya. He is the author of "Twelve Meanings of Zhang Changshi's Writing Method".

The twelfth year of the Dali calendar (777):

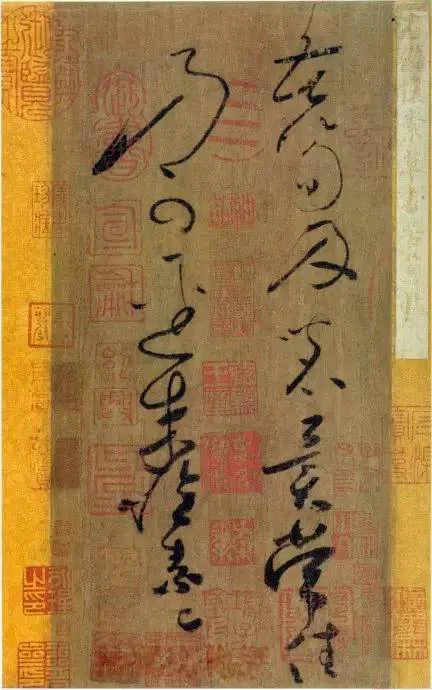

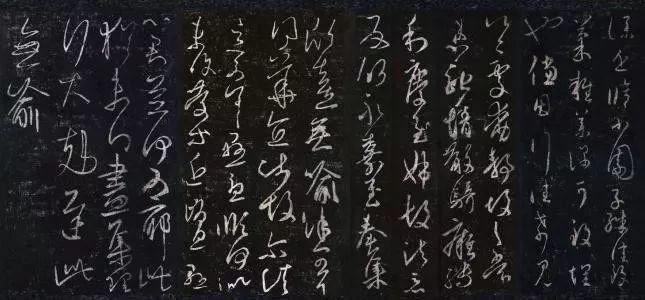

Monk Huaisu (737?—?), whose courtesy name was Zangzhen and whose common surname was Qian, was from Changsha. He is good at cursive calligraphy and is also addicted to alcohol. Together with Zhang Xu, he is known as "Dian Zhang Zui Su". This year's book is "Zi Xie Tie" (this volume may be considered a facsimile, not written by Huai Su. It is now in the collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei). There are also "Bitter Bamboo Shoots Tie" (now in the Shanghai Museum), "On Calligraphy Tie", "Eating Fish Tie" (suspected to be a forgery), "Dacao Qianzi Wen", "Notre Dame Tie", "Hidden Genuine Tie", " "Lv Gong Tie" (the last four are all engravings) have been handed down from generation to generation.In the fifteenth year of Zhenyuan (799):

Huai Su wrote "Xiao Cao Thousand Character Essay".

Lu Yu (733-804), courtesy name Hongjian, was a native of Jingling, Fuzhou. There is a section in the "Farewell Biography of Huaisu" that describes Huaisu and Yan Zhenqing's discussion of cursive script, and important concepts such as "bibi road" and "house leakage mark" appeared for the first time.

Han Yu (768-824), whose courtesy name was Tuizhi, was a native of Heyang, Henan. The author's "Preface to Master Gao Xian" discusses Zhang Xu's cursive script, which is extremely valuable.

Monk Gaoxian (?—?) was from Wucheng. Among the books are fragments of "The Thousand Character Essay" (now in the Shanghai Museum).

Five Dynasties: AD 907-960

Monk Yanxiu is good at cursive calligraphy.

The first year of Qianyou (948):

Yang Ningshi (873-954), courtesy name Jingdu, also known as Hongnong, Guanxi old farmer, and Huayin. At that time, he was called Madman Yang. This year's book "The Daily Life of Immortals" (now in the Palace Museum). There is also "Xiaretie" handed down from generation to generation.

Song Dynasty: 960-1279 AD

In the third year of Chunhua (992): Emperor Taizong of the Song Dynasty, Zhao Kuangyi, ordered Wang Zhu and others to engrave the names of all the Dharma books of the past dynasties on jujube woodblock tablets, which is called "Chunhua Pavilion Tie".

Su Shi (1036-1101), courtesy name Zizhan, also known as Dongpo Jushi, was a native of Meishan, Meizhou. Among the books are "Xi Lou Tie" (engraved edition still exists today).

From Huangyou to Jiayou (1049-1063): Pan Shidan added and subtracted from "Chunhua Pavilion Tie" and laid stones in Jiangzhou, which became "Jiang Tie".

In the second year of Joshua's reign (1095):

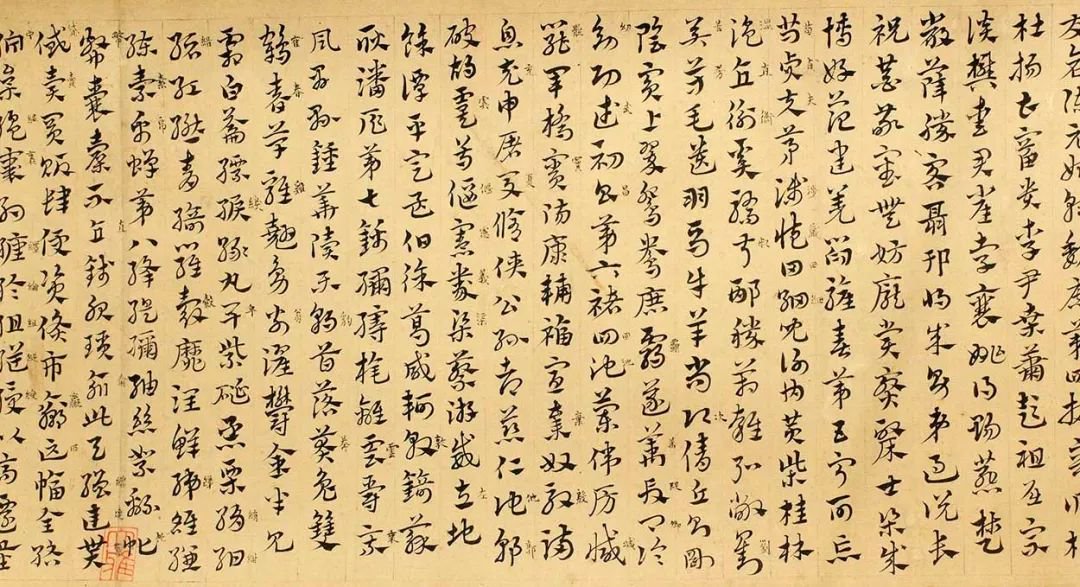

Huang Tingjian (1045-1105), whose courtesy name was Lu Zhi, also known as Fu Weng and Taoist of the Valley. This year's book "The Biography of Lian Po and Lin Xiangru" (now in the Metropolitan Museum of New York, USA).